The Yuan and its conversion into an international reserve currency

China is growing at 6.9%, one of the highest rates in the world, and is attempting to enter the big leagues, beginning with internationalization of the Yuan.

- Análisis

Be careful what you wish for 點石成金

The early days of 2016 were accompanied by serious market problems. Among these there is China and the Shanghai stock market. For a reader who is not aware of when and how the Shanghai stock market was opened and above all the reasons for doing this, it is unclear whether there be a collapse of the Chinese economy or an exchange rate war in which China has decided to weaken the dollar, above all if one reads the English language press. In fact, China is growing at 6.9%, one of the highest rates in the world together with Turkmenistan and Ethiopia, and later followed by Panama and Bolivia and is attempting to enter the big leagues, beginning with internationalization of the Yuan.

With this end in view, teller windows operating in Yuans were established around the world. The Atlantic Council says: "The internationalization of major currencies tends to follow an evolutionary process in which a currency evolves from being merely an instrument for invoicing and trade to a means of investment and eventually a staple of central bank reserves." [i] Thus what followed the step of turning it into a means of trade was to transform it into a means of investment through the liberalization of the Yuan in the offshore market. As a means of trade, the Yuan moved from representing 7% of Asian commerce with China in 2012 to 37% in 2015, according to SWIFT. It is employed in 37% of commercial payments from the United States and 33% from Europe. It is the second most employed currency in trade financing and the fifth in investment financing in 2015. Sixty central banks now have Reminbi in their international reserves.

The Yuan is a currency with a controlled exchange rate onshore, with a 2% floating band since July of 2012 and before that 1% since 2007. Hence, the establishment of a free currency market offshore opened up a parallel market. The offshore market is a free floating market and international investors can operate in the futures market without limits. This creates the possibility of arbitration between both markets, onshore and offshore. The biggest Yuan offshore market is Hong Kong while the most significant is London, seat of the Euromarket of the main world currencies. The London stock market price is the benchmark for the world currencies now that they are quoted as commodities. For a currency to be classified as an international reserve, all currency trade restrictions must disappear and the world market alone must define its value.

There are five hundred foreign enterprises registered as Qualified Foreign Institutional Investors (QFIIs) that, since November of 2014, may also operate through Hong Kong in what is called the Shanghai-Hong Kong Stock Connect. The stock connect allows the use of local brokers in the other market and payments to be made in local currency. This established a window for external operators to enter the Chinese market up to an amount of 48.660 billion US dollars annually.

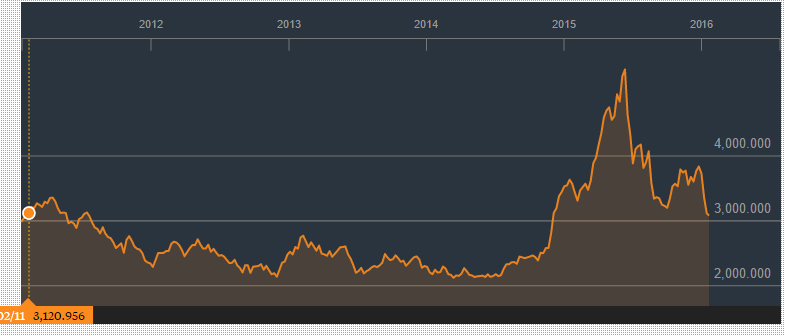

The opening of the Shanghai market to that of Hong Kong for world investors in November of 2014 had an immediate impact on the CSI index of capitalization. The fastest stock market bubble in the world was seen. Between November 7, 2014 and June 12 2015, the CSI index went from 2,502 to 5,335, the day in which the market "burst". This more than doubling of the index (113% increase) and its celebration by the international press, then turned into the metaphor of the Chinese economy when the western press began to treat it as if this were the New York or London markets, whose indicators today are, by the way, also meaningless to help us understand the economy of those countries (See graph 1)

GRAPH 1. Shanghai market index CSI 300

Source: Bloomberg

In the week of June 15, 2015, when Yellen, president of the FED should have declared whether interest rates would rise or not, the CSI300 index crashed from 5,335 to 4,637 on June 19 and to 3,663 on July 8. In less than a month, the CSI300 Shanghai index lost 31% of its value. A month later, on August 24 there was a further fall of 8% adding an overall loss of 38% from its June peak. This variation is clearly speculative given the speed of the fall.

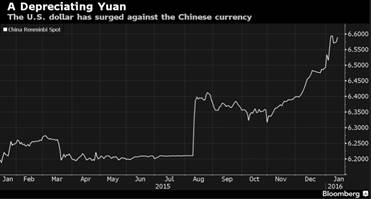

The question is: who bet that there was a bubble and that the market would not hold at that level? The response is that whoever bet on the fall was the same agent who entered the market when it opened in November 2014 and produced a bubble in a tiny market by injecting significant amounts of money. Whoever did this worked from the dollar into the Yuan and was confident that the fall of the stock market would be accompanied by massive withdrawals of dollars from the Chinese economy (onshore) and so bet against the Yuan (offshore). The exchange rate of the Yuan in August 2015 lost value, from 6.20 Yuans per dollar to 6.40 Yuans per dollar. The attack against the stock market was simultaneously reflected in an attack against the rate of exchange (See graph 2). The cost for the People’s Bank of China was 94 billion dollars according to the Financial Times (September 7, 2015 1:44 pm: China's foreign exchange reserves fall by record 94bn).

GRAPH 2: The devaluation of the Yuan

There are four New York hedge funds that operate in the Yuan market. They are: ESG, of the Carlyle Group (Bush family), Passport Capital, Omni Partners and Odey Asset Management, according to Bloomberg. Excepting ESG, the others are funds with less than 5 billion dollars. There might be other hedge funds that Bloomberg has not identified. The sure bet against a currency when the stock market of a country is opened up to foreign investors can sound extravagant, unless the agent is an investor in that market and knows when he is going to withdraw. In this way, an agent can make with little money a bet ten times bigger and if it works, the gambler can get a huge profit (See the movie The Big Bet). The cost of the bet is paid by the country whose money and market are under attack.

Yuan bonds were issued in London in 2013 as part of the internationalization of the currency. (See Ugarteche and Noyola, 19/1/14 (“La City de Londres, capital global del Yuan” - www.alainet.org/es/active/70610). Once the Yuan was accepted there, the opening of the Shanghai stock market gave wings to the currency market based in London. The only thing left to be done was the commitment that China would completely liberalize its foreign exchange market.

In order for this to happen, China put as a condition that its currency be included in the IMF basket of SDR currencies. As the fifth currency in the Special Drawing Right (SDR), a unit of account composed of several currencies established to maintain value, the Yuan received the blessing to operate freely in the international exchange markets, and so fulfilled the final requirement to become an international reserve currency. Thus, on November 30, 2015, the IMF accepted the Yuan in the basket of SDRs adding to the dollar, the yen, the euro and the Pound Stirling. Together with this, on December 18, the US Congress approved the IMF voting system reform, perhaps one of the most important reforms of the Fund since its inception. The new SDR contains a value of 11% of the Yuan, establishing it in third place, below the dollar and the euro. The renewed SDR will go into effect on October 1, 2016 (See table). With respect to the quota system of the IMF, the big losers are the European countries with the exception of Spain. Japan will continue maintaining the second place. China is in third place in the number of votes. Brazil moves up four positions, and India and Russia entered the list of the ten most influential. It should be noted that the United States will continue to exercise the veto.

SDR 2005 - 2015 Weights of currencies

| 2015 | 2010 | 2005 |

US dólar | 41.73% | 41.9% | 44% |

Euro | 30.93% | 37.4% | 34% |

Libra | 8.33% | 11.3% | 11% |

Yen | 8.09% | 9.4% | 11% |

Yuan | 10.92% | --- | --- |

Source: IMF

The conditions the IMF established for the Yuan becoming an international reserve currency are: 1) the opening of their interbank markets and those of currencies (disappearing the onshore/offshore division and the flotation band) to international financial institutions, 2) improving statistics on currency reserves, and 3) a flexibilisation of exchange rates in order that market forces influence them. These conditions, accepted and signed on November 30, were ratified when the US Congress accepted the change to the voting system two weeks later in December. As strange as it may seem, the exchange rate impact of this decision has been the depreciation of the Yuan, something that under normal conditions appears totally illogical. The "money of the people" went from 6.40 in August to 6.60 at the end of December. The strengthening of the dollar and the repeated attacks to sink the emerging country currencies resulted in 2015 in a depreciation of the Yuan by 6.82%, the Rupee 8.97% the Rouble 10.78% , the South African Rand 43.67% and the Real 54.08%.

The raising of interest rates by the FED on December 17, 2015 had an immediate effect on the American markets, as well as in Europe and Latin America, but not so in China, Korea, India and other Asian countries, where the effect was felt with a two week lag at the end of the year.

Nevertheless the bet was aimed at a great fall of the Yuan and not even its inclusion in the SDR was able to prevent it. Crispin Odey, who controls Odey Asset Management, said in September 2015 that "the Yuan should fall by at least 30% (Bloomberg, "Hedge Fund That Called Subprime Crisis Urges 50% Yuan drop") Mark Hart of Corriente Advisors bet against the Yuan and said it should depreciate 50% according to the same note.

The cost for China of the internationalisation of the Yuan is their having left the value of their currency in the hands of speculators who will do whatever they can to prevent the Yuan from advancing in its new role as an international reserve currency. Looking at the depreciation figures above, the press is making much ado about nothing; even if the loss of 5% of its reserves in the year has been a trend changer, this was to defend the Yuan, and it could be said that it was successful.

It would be good if someone at the People’s Bank of China read about the way in which the United States placed the dollar as a dominant international reserve currency in 1945, eliminating the sterling zone and the role of the pound. The Americans forced the Brits to open the capital account at the end of the war and its international reserves were decimated by January 1946, when they had to close it again. After that the pound lost its relevance as an international reserve currency. This is set out in the book The Battle for Bretton Woods by Ben Steil. One has to keep in mind that more value is destroyed in devaluation than on a battlefield, as we can see in the attacks against the Rouble, the Real and the South African Rand over the past eighteen months.

(Translated for ALAI by Jordan Bishop)

- Oscar Ugarteche, Instituto de Investigaciones Económicas UNAM, SNI/Conacyt. Coordinator of the Observatorio Económico de América Latina, Obela.org.

Jorge Arturo Luna is a collaborator of Obela

[1] RENMINBI ASCENDING How China’s Currency Impacts Global Markets, Foreign Policy, and Transatlantic Financial Regulation, Atlantic Council, City of London, Thomson Reuters, Standard and Chartered, 2015.

Del mismo autor

- El multilateralismo bipolar 08/03/2022

- Bipolar multilateralism 07/03/2022

- What does 2022 bring? Uncertainty 31/01/2022

- ¿Qué trae el 2022? Incertidumbre 31/01/2022

- The most expensive Christmas of the century... (so far) 20/01/2022

- La navidad más cara del siglo (hasta ahora) 20/01/2022

- Lo que pasó en el 2021 10/01/2022

- What happened in 2021 10/01/2022

- Estados Unidos: el elefante en la habitación 08/11/2021

- The elephant in the room 07/11/2021