Is another Internet possible?

There are new challenges for the political-economic system and social coexistence, that our societies have not yet been able to process properly.

- Análisis

| Article published in ALAI’s magazine No. 503: Hacia una Internet ciudadana 28/04/2015 |

Just 25 years ago, most people had never used a computer, seen a mobile phone or heard of the Internet. These technologies are now so embedded in everyday life, that our ways of doing, living, working, consuming, interacting and organizing, are undergoing rapid transformation, bringing many benefits. The Internet is already the leading global database for purposes of education, knowledge, work, consumption and others; but for the same reasons, there are fundamental issues of human rights and public interest, related to control and decision-making power. Hence, there are new challenges for the political-economic system and social coexistence, that our societies have not yet been able to process properly.

The invasion of communication privacy is perhaps one of the most obvious examples, since Edward Snowden's revelations about massive spying by the US National Security Agency (NSA). But there are many more areas where new issues are emerging, including: potential discrimination in automated screening of candidates for jobs, education, credit, and others; the loss of labor rights in the new "sharing economy"; or the excessive power of a single private transnational company – Google – to determine what is visible and what is not in the world’s biggest and most consulted data and knowledge base – i.e. the Web. This means that decisions on the development of Internet applications and usages have implications for human rights, justice, social and economic equity, and democracy, which require a framework of public policies and regulations at the national and international levels.

Decentralization or concentration

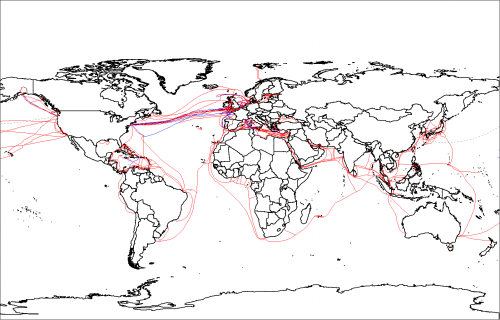

There is no doubt that the Internet, which was initially developed as a relatively decentralized system, has allowed the flourishing of countless initiatives of creativity and innovation. It is perhaps the first time that the population has access to freely participate in the development of a cutting-edge technology, rather than simply being a user. With its adaptability to different scales, this technology has demonstrated its ability to empower citizen and community initiatives, under their own control. It has also helped to democratize access to information, communication and knowledge; and allowed the proliferation of spaces – whether open or closed – for the free exchange of ideas, knowledge and creations, where a sense of common property and self-management prevails.

Under concepts such as "the commons", free software and the culture of shared knowledge, many alternative technology initiatives are being developed, including free social networks, messaging services, blogging platforms, security systems, even an alternative system of domain names, Open Root, which is independent of the ICANN[i] system.

Nevertheless, in parallel there has been another contrary trend towards concentration and centralization. And, because of the so-called "network effect", where users converge towards the more successful service, the Internet has also tended towards the formation of large monopolies, with an unprecedented economic accumulation, and the consequent concentration of power[ii]. The "raw material" of this enrichment is the accumulated data (personal and other) that users – often involuntarily – deliver to these companies in exchange for "free" services; data that are sold to advertisers, which are the preferred clients of these companies; while users, as potential consumers, become the "product". Moreover, to reinforce their control, public spaces are being fenced-in behind "walls" within the private platforms of online social networks, where the rules are defined by the corporate supplier.

Alongside this second trend – and we now know it’s in direct collusion – is the universalization of surveillance by security agencies, mainly of the US and its four Anglophone allies (Britain, Canada, Australia and New Zealand – which together make up the so-called 5 eyes), ignoring any geographical, legal or ethical limit. Their goal is to collect all possible information from all over the world, on all topics and keep it indefinitely. It’s a known fact that other national governments also venture into such activities to a lesser or greater extent, within or outside the law, though not on such a massive scale. Moreover, at least 30 countries are developing cyber weapons, which could steer us towards a situation of war in and through the Internet, which brings the risk of escalating to other levels of war.[iii]

Between these two opposite trends – decentralization, or concentration/ monitoring/ cyber weapons – the balance is tilting dangerously towards the latter, with potentially serious consequences for human rights and social and economic justice, and even democracy itself. This is because market forces push strongly toward concentration; but also because the technological development of the Internet has not properly prioritized the security of users. Also, there are few measures in terms of legislation or public policies designed to bring some sort of order in this area. There are even cases where legislation goes in the opposite direction, sacrificing the security and privacy of users, supposedly to protect people from terrorism, although without evidence that it is effective.

Legal battles

Several recent initiatives are reviving the debate about digital rights in the world. Many governments have adopted policies to ensure net neutrality. Among the most advanced legislation on Internet rights is that of Brazil and some countries of the European Union. Moreover, Germany and Brazil are leading an initiative on privacy at the UN, in the wake of the Snowden disclosures, one result of which is that the UN Human Rights Council recently appointed a special rapporteur on privacy.

Inevitably, sooner or later, the defense of digital rights will involve confronting the excessive power of the Internet’s large transnational corporations. As another example of this power, on April 21, 2015, Google unilaterally changed its search algorithm for mobile, so that searches no longer take into account the sites considered "mobile-unfriendly". In other words, the site’s content, reputation or popularity no longer count, but rather the ability to install mobile technology, which is a disadvantage for many low-income sites.

Keep in mind that over 60% of searches on the Web globally (and about 90% in Europe and Latin America) go through Google. The company has the power to determine what content is on web users’ horizon and what they will never find. But, with what legitimacy has it taken on this power? Just days before, the European Union’s antitrust commissioner formally accused Google of abusing the dominant position of its search engine, because its secret algorithms favor certain content over others in search results. Google has announced that it will litigate the case in court and the trial could last for years. How many governments will have the ability to take on giants like Google, and even if they do, how much will they affect the power of these businesses? Remember that Google also has Gmail, the second e-mail service in the world; the Android system that captures 76% of the smartphone market; Youtube, which dominates online video; and it is by far the world's largest vendor in the huge market of online advertising.

Meanwhile, it is not only the private corporations that are being targeted for the abuse of rights on the Internet, but also certain governments and their security agencies. A study just released by the Global Commission on Internet Governance, entitled "Towards a Social Compact for Digital Privacy and Security,"[iv] notes the current risk of erosion of confidence in the Internet and warns that "Individuals and businesses must be protected both from the misuse of the Internet by terrorists, cyber criminal groups and the overreach of governments and businesses that collect and use private data.” (p. 9). In accordance with the right to privacy recognized in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, the study states that "the role of government should be to strengthen the technology upon which the Internet depends and its use, not to weaken it." (p. 10 ). The report insists on the recognition of privacy as a fundamental human right; and calls for greater transparency and accountability of governments; and proportionality in monitoring, in accordance with national and international human rights law. It also demands more responsibility from companies that collect user data, both to ensure its secure handling, and to properly inform and consult users on its usage.

Chaired by former Swedish Prime Minister and Conservative Party leader Carl Bildt, the Global Commission on Internet Governance is composed of a high-level group of 29 people with influence in Internet policy circles, including former senior US and British security and intelligence officials. It is quite significant that a group that is mainly from the establishment recognizes that the balance between national security interests and privacy is being lost; and that undermining the safety of users implies favoring crime and even terrorism. However, in its recommendations of mechanisms to forge ahead, the Commission defends the current "multistakeholder" model of governance, which in reality has been mostly unresponsive to democratic standards.[v]

In recent times, there have also been several private lawsuits in European courts to determine to what extent existing rights should be respected in the digital domain. And on several occasions, it has turned out to be a legal system willing to take on governments and private corporations to set strong precedents in defense of human rights. Such cases include a European Court of Justice ruling against Facebook for the security and treatment of data of European users, in view of its cooperation with intelligence agencies on programs like Prism. The same court also supported the "right to be forgotten" (i.e. to request removal of personal data from search engines). In another case, a court in the United Kingdom recognized the right of users of Apple's Safari browser to seek redress from Google for having retained and sold data about their private web browsing habits without authorization.[vi]

Meanwhile, in 2014, the same European Court partially overturned the 2006 EU Data Retention Directive, considering that forcing communications providers to retain all the metadata (i.e. who communicates with whom) unduly interferes with the fundamental right to privacy.

As for the countries of the South, few would be able to confront Internet corporations in the courts. In fact, rather some are opening their doors further, accepting for example the Internet.org Facebook initiative. Internet.org supposedly extends access to the Internet in poor areas from mobile phones, but in practice amounts to "a poor Internet for the poor", that right from the beginning binds them to corporate platforms, and this, in flagrant violation of the principle of net neutrality. So far in Latin America, only Chile has stood firm to deny the entry of Internet.org.[vii] Of course, it is important to develop alternatives for impoverished communities to obtain access to technology, but there are other options that do not involve dependence on corporate spaces, such as the guifi.net initiative in Catalonia, which has received awards for interconnecting communities with self-managed equipment at a very low cost.

Towards a Social Forum of the Internet

There is a growing understanding that we can hardly begin to alter current trends in the configuration of power and the Internet governance system if a broad social movement to exert pressure to this end is not built. As a contribution to this purpose, in early 2015, various organizations launched the idea of an Internet Social Forum (ISF) as a themed process linked to the World Social Forum (WSF). More than 80 organizations[viii] have joined the initial appeal and the initiative was discussed at the WSF in Tunisia, last March.

The ISF[ix] is presented as a space to debate "the Internet we want and how to build it, before the knowledge and access-to-information revolution is irretrievably captured by corporate interests and security agencies that will deepen the nexus of corruption between politics and money."[x]

The intention is to bring in a wide range of organizations, social movements and social activists who share this goal, as the Internet has become a tool, a space for exchange and an indispensable reference for organizational work and social causes. The proposal is to create with them a democratic mechanism for the ISF’s organization, and among the first steps, determine the place and date of the Forum.

Why the format of a Social Forum? The call states that the Internet Social Forum (ISF) is inspired by the processes of the World Social Forum (WSF) and its visionary proclamation that "Another world is possible", adopting the motto "Another (people’s) Internet is possible". Recalling the WSF’s Charter of Principles, which appeals to a globalization process different from the one "commanded by the large multinational corporations and by the governments and international institutions at the service of those corporations' interests", the ISF calls for "an Internet from below which is controlled by the people – including those not yet connected."

In the English edition of ALAI’s magazine on “Towards a people’s Internet”, several of the people linked to the ISF process explore some of the important issues in building a people’s Internet, or a citizens’ Internet, that will be more just, equitable and democratic.

(Translation: Carmelo Ruiz-Marrero).

Sally Burch is a journalist with ALAI.

Article published in: Latin America in Movement 503, ALAI, April 2015. “Towards a people’s Internet” http://www.alainet.org/en/revistas/169787

[i] ICANN: the Internet Corporation for Assigned Names and Numbers is the body that controls this system globally.

[ii] See Sally Burch “How can Internet be de-monopolized? Interview with Robert McChesney”, Latin America in Movement, No 494 (April 2014), http://www.alainet.org/publica/494-en.phtml

[iii] See the article by Prabir Purkayastha in ALAI: Towards a people’s Internet http://www.alainet.org/en/articulo/169780.

[v] See the article by Norbert Bollow in ALAI: Towards a people’s Internet http://www.alainet.org/en/articulo/169782.

[vi] On the legal cases mentioned see: Julia Powles, Data Privacy: the tide is turning in Europe – but is it too little too late? The Guardian, http://bit.ly/1c0EOUQ

[vii] See the articles by Parminder Jeet and María del Pilar Sáenz in ALAI: Towards a people’s Internet http://www.alainet.org/en/articulo/169781, http://www.alainet.org/en/articulo/169792.

[x] Tunis Call for a People's Internet, http://www.internetsocialforum.net/?q=Tunis-Call_for_a_Peoples_Internet

Del mismo autor

- Which digital future? 27/05/2021

- ¿Cuál futuro digital? 28/04/2021

- Desafíos para la justicia social en la era digital 19/06/2020

- É hora de falar de política de dados e direitos econômicos 06/04/2020

- Es hora de hablar de política de datos y derechos económicos 01/04/2020

- It’s time to talk about data politics and economic rights 01/04/2020

- 25 de enero: Primer día de protesta mundial contra la 5G 23/01/2020

- January 25: First global day of protest against 5G 23/01/2020

- « En défense de Julian Assange » 02/12/2019

- "En defensa de Julian Assange" 29/11/2019

Artículos relacionados

Clasificado en

Comunicación, FSM

- Jorge Majfud 29/03/2022

- Sergio Ferrari 21/03/2022

- Sergio Ferrari 21/03/2022

- Vijay Prashad 03/03/2022

- Anish R M 02/02/2022

Internet ciudadana

- Nick Bernards 31/03/2022

- Paola Ricaurte 10/03/2022

- Burcu Kilic 03/03/2022

- Shreeja Sen 25/02/2022

- Internet Ciudadana 16/02/2022