The Bandung pledge renewed

- Opinión

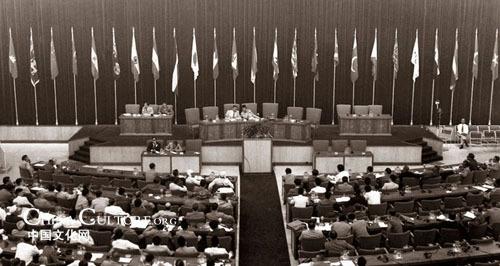

The 60th anniversary of the historic Bandung conference of 1955 was marked by a short but meaningful ceremony, on 24 April, when top political leaders from over 40 countries, led by Indonesian President Joko Widodo and officials from international organisations, walked from Savoy Hotel to Merdeka, in Bandung, Indonesia. Among the leaders present were the Presidents of China, Zimbabwe and Myanmar, the Prime Ministers of Malaysia, Nepal and Egypt, and the King of Swaziland. They had just concluded a two-day Asian-African Summit conference in Jakarta, with the theme South-South Cooperation for Peace and Prosperity.

Sixty years ago, on this same date, a small but powerful group of men and women took the same walk and then launched a movement that snowballed into a united anti-colonial and post–colonial movement. It was when the Bandung conference of Asian and African leaders took place, all of whom had just won Independence or were on the verge of doing so.

Bandung 24 April 1955 saw giants like the host, President Sukarno of Indonesia, Prime Ministers Chou En Lai of China and Jawaharlal Nehru of India, President Gamal Abdel Nasser of Egypt, U Nu of Burma and some leaders of Africa, coming together to discuss the need for newly independent countries to unite and fight for their common interests. They adopted the Bandung principles that included respect for national sovereignty and self-determination, equality of all nations and abstention from use of force or exerting pressure on countries.

South-South multilateral cooperation

The 1955 Bandung Asian-African Conference marked the first attempt at multilateral cooperation between developing countries “on the basis of mutual interest and respect for national sovereignty”. The Bandung Conference brought together the generation of gifted and courageous Asian and African leaders who had won or were in the middle of winning their battles of independence. The final communiqué from Bandung in 1955 contained the 10 principles of the “Bandung Spirit”, outlining the basic principles for South-South cooperation in the efforts to promote peace and cooperation in the world. These principles remain as valid as ever in today’s world which is in economic and political turmoil.

The solidarity that the Bandung conference leaders forged then was later to give rise to the Non Aligned Movement (NAM) and the Group of 77, the two big umbrella bodies under which the developing countries have been putting forward joint positions and participating in many international fora in which they face their former colonial masters, now known as the North.

The rationale for developing countries grouping together is still as relevant today as 60 years ago. There are still some nations that are struggling to be born, such as the Palestinians in their long-standing battle against occupation and suppression, as was highlighted at the 2015 Jakarta-Bandung summit, where it was obvious that the continuing occupation of Palestine lands and their unfulfilled fight for an independent state was a big piece of “unfinished business” of the Asian African 1955 Bandung conference.

Though there has been some progress in the economies of developing countries, much of this progress was in the one and half decades since 2000. However, the rather high growth rates in these years may be seen to be quite exceptional, due to high demand from the advanced economies plus the new increased demand from some emerging economies. This resulted in high demand and high prices of commodities, which is the main reason why many developing countries, which are still commodity dependent, were able to enjoy high economic growth.

This commodity dependence was barely noticed while there was a commodity boom since 2000; but the dangers and weaknesses of relying on commodities is once again haunting the developing world, now that the developed countries are suffering from an economic slowdown. It is thus imperative to address once again the problem of commodities, the fluctuating demand and the need for stable and decent prices, and also the need to add value to raw materials and to climb the manufacturing ladder based first on natural resources.

Another major problem is the liberalisation of capital flows. In the Bretton Woods era, capital could move only if it was linked to trade and foreign direct investment flows. But with financial liberalisation starting in OECD countries and then more recently taking place in developing countries, there has been a tremendous upsurge in capital flows arising from funds searching higher yields. Thus many developing countries have endured massive inflows and now outflows of short term and speculative capital, with resulting volatile fluctuations in exchange rates, and in drawdown of their foreign reserves.

The current crisis situation reveals that the much touted “convergence” between developing economies and developed countries is not really taking place, or at least not fast enough. Most developing countries are still dependent on the performance of developed countries and their institutions and funds.

Meanwhile, developed countries still control the levers of the financial, monetary and economic systems. The IMF and World Bank remain under their control, with the promises for governance reform (changes in quotas) being unfulfilled, and the leadership of these two institutions still remain in the ambit of the US and Europe. In other words, the global economic institutions and structures are still dominated by developed countries, whilst of course global military power resides in the same ex colonial masters.

There is still need for developing countries to coordinate among themselves and cooperate in the trade, investment and financial and technological areas, as they are still dependent on the major countries; they still have common interests, which they have to defend and promote. The forms of dependence and subjugation may have changed in some ways but the reality remains: though the developing countries won political independence, the goal of decolonisation still remains to be fulfilled.

For Asia and Africa as well as Latin America, the battles they began 60 years ago for economic decolonisation remain relevant and as valid as ever. The financial and economic systems of the world have become more complex and sophisticated, including the new financial instruments that are difficult to understand let alone regulate, and the developing world is at the receiving end of their workings. For the South, the struggles that started at Bandung 1955 and later at the establishment of NAM and the G77 are still being waged by their successors today.

A new world order

The Indonesian President, in his opening address at the 2015 Summit, pointed out the on-going and even worsening inequalities in the international systems, and called for establishing a new world order where the developing countries have an equal say and enjoy their fair share of the benefits.

Such a new and more equitable world order would enable the developing countries to contribute to the solutions to the multiple crises of global finance and economy, food security, unfulfilled social development, energy and climate change. The developed countries would change their unsustainable patterns of production and consumption, and assist the developing countries through financial resources and technology transfer to embark on new sustainable development pathways.

South-South cooperation, based on solidarity and mutual benefits, will play an increasingly important role. There is much to be done politically and concretely in this area. It is noteworthy that the theme of the 2015 Asian-African Summit was “strengthening South-South cooperation to promote world peace and prosperity”.

A new trend in South-South gatherings such as this one is that criticism of the ways of the West in dominating the South is now combined with announcements of how the developing countries are organising various ways to rely more on one another, including creating new institutions.

Bandung 1955 was a landmark event that launched many good developments for the newly independent countries. Bandung 2015 could also prove to be a landmark event that catalyses further breakthroughs in South-South cooperation, which together with our better performance in multilateral relations, will implement the building of the new world order that our first generation of leaders were dreaming of.

- Martin Khor is Executive Director of the South Centre. www.southcentre.int

(This article is based on a statement made by the Southcentre at the Jakarta-Bandung conference).

Article published in ALAI’s Spanish language magazine: América Latina en Movimiento, No 504 (May 2015), titled: “60 años después: Vigencia del espíritu de Bandung”. http://www.alainet.org/es/revistas/169851

Del mismo autor

- Trade pacts may hinder regulation 07/11/2018

- Warnings of a new global financial crisis 12/06/2018

- The new CPTPP trade pact is much like the old TPP 13/03/2018

- Stock market turmoil may expose flaws in global finance 14/02/2018

- South should prepare for the next financial crisis 02/01/2018

- Donald Trump dominated the year by using US clout to change global relations, and not for the better 27/12/2017

- Yet another looming financial crisis 19/10/2017

- US pull-out from Paris deal: What it means 07/06/2017

- Reflections on World Health Day 21/04/2017

- The Need to Avoid “TRIPS - Plus” Patent Clauses in Trade Agreements 28/03/2017