Treaty on TNCs and human rights: Touching a nerve

The negotiation has revealed the conflicting – but sometimes coinciding – interests among the major actors: states, corporations and affected communities.

- Análisis

Since 2015, there has been an annual negotiation at the United Nations’ Palais des Nations in Geneva that touches the very nerve centre of corporate capitalism. This event stems from the June 2014 United Nations Human Rights Council (UNHRC) Resolution 29/6 that set up an intergovernmental working group to elaborate a legally binding instrument to regulate transnational corporations. It was a historic initiative as it demonstrated that corporate rule – which many still see as unquestionable – can be challenged and confronted.

It is, unsurprisingly, a negotiation that has been contested every step of the way, revealing the often conflicting – but sometimes coinciding – interests among the three major actors: states, corporations and the affected communities, social movements and civil society organisations (CSOs).

This trajectory sees the convergence of diverse paths.

For states – assuming a new historic responsibility to put a Binding Treaty in place that addresses the acknowledged gap in human rights law, the architecture of corporate power and impunity, and access to justice. For corporations, the repeated defence of the status quo – legitimising corporate violations of human rights and profits before peoples’ rights. And for affected communities and social movements – persistent resistance, building law from below and sustaining pressure on governments.

Addressing systemic corporate impunity

Ever since transnational corporations (TNCs) became major global actors, affected communities, factory workers and social movements have resisted this corporate economic model.

By 2000, communities and workers worldwide had protested against TNC crimes – including such iconic cases as the Union Carbide pesticide plant’s poisonous gas leak in Bhopal in 1984; Shell’s ruptured pipeline in Bodo Nigeria (2008–2009); Chevron’s dumping of crude oil in Ecuador (1964–1992); European Corporations’ (Fossil Fuels/Energy, Agriculture & Manufacturing) blocking of significant reductions in CO2 emissions; and British Petroleum’s (BP) Deep Water Horizon explosion (April 2010) in the Gulf of Mexico.

____________________

____________________

While the resistance of affected communities has been a constant challenge to the operations of TNCs and their human rights violations, it was the joint convening of the Permanent People’s Tribunal (PPT) Sessions by the Hemispheric Social Alliance (HSA) and the Enlazando Alternativas on European Corporations in Latin America (2004–2010) that kick-started a new process of bringing the different movements together and developing a shared analysis of the corporate violations of human rights.

In the process of sharing experiences of 46 cases in three sessions, they not only pointed to the specific corporate violations of human rights but also identified their systemic character.

The verdicts identified an ‘architecture of impunity’, generated by different trade and investment agreements and the global institutions of the World Trade Organization (WTO), the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the World Bank, that legitimised and prioritised protections and privileges to corporations over the human rights of communities and workers.

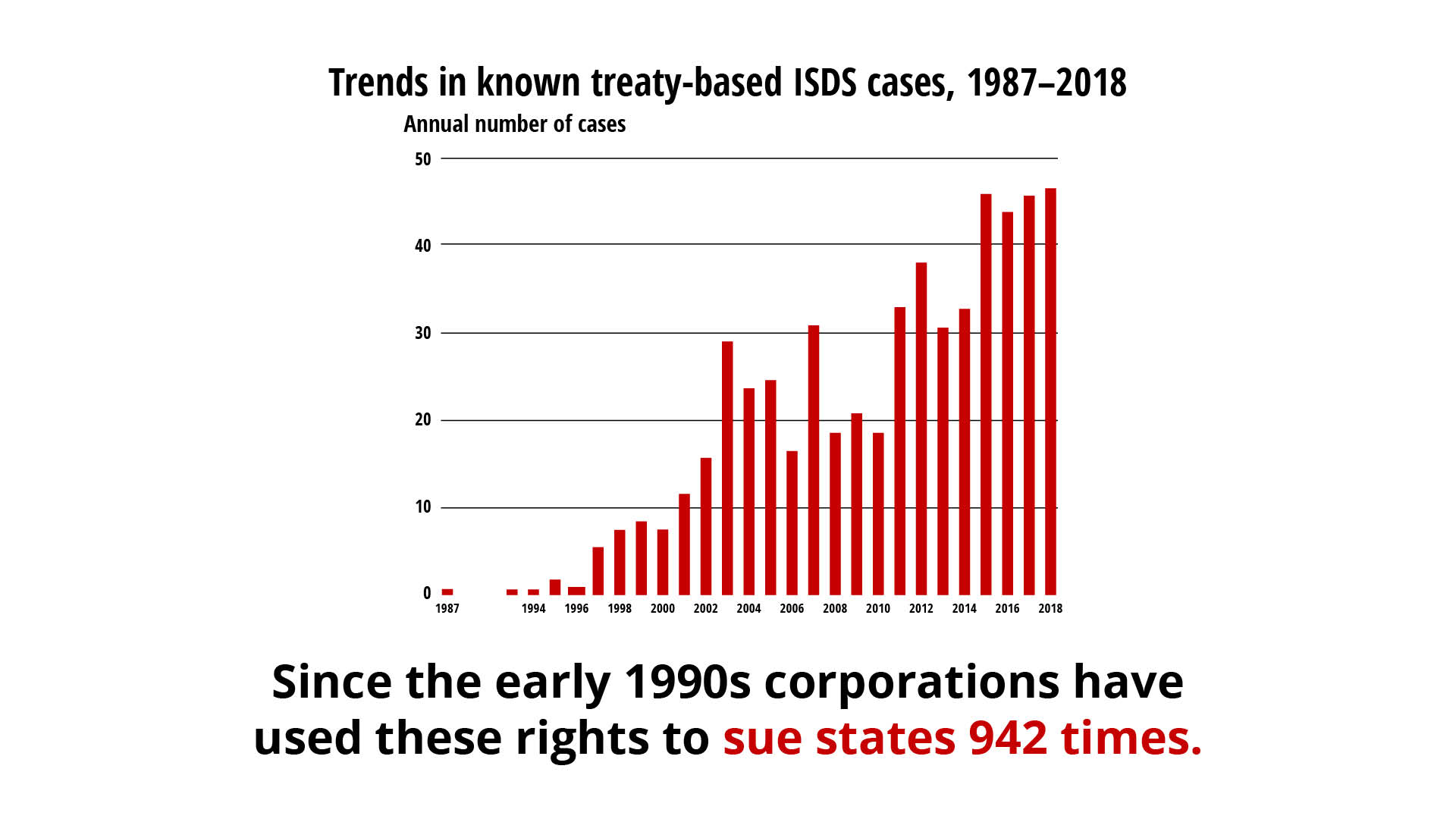

This notably includes the Investor to State Dispute System (ISDS) whereby TNCs can unilaterally sue states for actions that affect their profits. The PPT Judgement in Madrid in May 2010 concluded that the human rights of people in Latin America and Europe faced an impenetrable wall of impunity and denial of justice in relation to TNCs’ operations. It noted that Global Corporate Rule had become entrenched – privileging profits above peoples’ rights and the protection of the planet.

ISDS cases since the 1990s. Source: UNCTAD (2019)

The PPT Judgement was a watershed in the movement towards an international binding regulatory framework for TNCs’ operations, calling for the United Nations Human Rights Council to draw up a compulsory code of conduct for TNCs and for affected communities and social movements to develop a mandatory legal framework in the context of international law – envisaged as ‘one of the first steps on the path to creating a different world order’.

The Global Campaign to Reclaim Peoples Sovereignty, Dismantle Corporate Power and Stop Impunity (Global Campaign) was established in 2012 following extensive consultation on how to develop a strategy addressing corporate impunity. It also initiated the development of a Peoples Treaty on Transnational Corporations.

The campaign had two main pillars – a judicial pillar preparing detailed proposals for a binding international regulatory framework for TNCs and an alternatives pillar advocating a more people-centred economy that would reclaim democracy and peoples’ sovereignty.

1970s Attempts in the United Nations to tackle TNCs (1970–2013)

First discussions on holding TNCs to account as they become increasingly powerful international actors. Calls from countries in the Global South for a new international economic order (NIEO.

1972 Chilean President Allende denounces corporations at the UN General Assembly

‘Corporations are interfering in the fundamental political, economic and military decisions of the states’ even though their activities ‘are not controlled by, nor are they accountable to any parliament or any other institution representative of the collective interest.’

1973 Allende killed in a military coup

1974 UN sets up a Commission on Transnational Corporations

UN sets up a Commission on Transnational Corporations and the United Nations Centre on Transnational Corporations (UNCTC)

1980s Globalisation and the dominance of ‘free market’ approaches

Sustained opposition to the UNCTC, most notably from the US government and corporate lobbies (International Chamber of Commerce (ICC) and International Organization of Employers (IOE). Proposed code of conduct for TNCs is dropped.

1993/1994 UNCTC dismantled

UNCTC dismantled, although elements of its work absorbed into the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD).

2000 UN Secretary General Kofi Anan launches the Global Compact

Global Compact is a voluntary partnership between the UN and TNCs, which legitimises a Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) non-binding regulatory regime for TNCs in relation to human rights.

2003 Reintroduction of binding regulation of TNC's

Attempt by the UN Sub-Commission for the Promotion and Protection of Human Rights to reintroduce the issue of binding regulation of TNCs fiercely opposed by the ICC and IOE.

2005 Professor Ruggie appointed by Annan to develop UN Guiding Principles

UN Human Rights Commission, ignoring the work of the UN Sub-Commission, adopts Resolution 2005/69, asking the UN Secretary General (Kofi Annan) to appoint a special representative to address TNCs’ impacts on human rights. Annan appoints Professor John Ruggie, who develops the United Nations Guiding Principles (UNGPs) – a voluntary reference framework with no legal obligations.

2011 United Nations Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights adopted

UNGPs adopted by the UNHRC along with mandates for implementation. Also set up a new working group of experts on Business and Human Rights, and a Forum on Business and Human Rights.

Overcoming the voluntary approach

By 2012, decades of attempts to regulate TNCs at the international level had been defeated. The main initial challenge was to overcome the international consensus in favour of a voluntary-led approach to corporate violations of human rights, which were embodied in the UNGPs developed by Professor John Ruggie and promoted as the mechanism for advancing human rights in relation to corporate violations and abuse. These were formally adopted at the UN in 2011 and claimed as the upper limit of human rights protection.

However, the track record of TNCs’ operations on the ground and the denial of justice to those affected by them gave little reason to expect anything different as a result of the UNGPs. Communities dealing with the devastating operations of TNCs insisted that self-regulation was not enough and demanded that only binding regulation could address the glaring gap in international human rights law in relation to TNCs.

While Ruggie, and particularly governments in the North, continued to insist that the UNGPs were the only deal in town, some governments in the South continued to call for binding regulation.

Kept alive by resistance by affected communities and social movements, this demand resurged in September 2013 when Ecuador and South Africa (supported by at least 85 governments) submitted a joint Statement to the 24th Regular Session of the UNHRC indicating the intention to re-open the agenda of a legally binding regulatory framework for TNCs.

The UNGPs have failed to stop corporate impunitySince 2011, affected communities and movements have repeatedly noted the inability of voluntary codes to address corporate violations of human rights and damage to ecosystems.

Analysis of the 101 world’s largest corporations in sectors known to pose a threat to human rights confirms this failure to implement the UNGPs:

Source: Corporate Human Rights Benchmark, 2018 Key Findings - |

Converging forces at the UN in June 2014

Ecuador and South Africa’s move was immediately backed by organisations of the Global Campaign, which voiced strong support. Soon afterwards, the Treaty Alliance was launched when members of the Global Campaign joined with several other human rights networks and organisations in Geneva to set up a broad coalition to work for a Binding Treaty.

The result was the historic vote in support of Resolution 26/9, which established an Open Ended Inter-Governmental Working Group (OEIGWG) ‘on transnational corporations and other business enterprises with respect to human rights; whose mandate shall be to elaborate an international legally binding instrument to regulate, in international human rights law, the activities of transnational corporations and other business enterprises...’.

Stop Corporate Impunity campaign marching outside UN in Geneva

The Resolution was carried by a small majority at the UNHRC – supported by governments of the Global South and opposed by each EU member state in the UNHRC as well as by states in which major TNCs are based – such as Japan, the Republic of South Korea and the United States. The vote thus made clear the geopolitical struggle that would mark every step of the way in the Binding Treaty process.

Feminists for a Binding TreatyIn 2015, civil society engagement in support of the Binding Treaty was further expanded with the setting up of the Feminists for a Binding Treaty. This network mobilises women and highlights gender perspectives in the advocacy for the Binding Treaty.

They focus on three key proposals:

Source: AWID et al (2017), Integrating a gender perspective into the legally binding instrument on transnational corporations and other business |

Binding Treaty process – a site of constant contestation

Since its launch in 2014, the UNHRC process has revealed the conflicts of interest and contradictions by the three main protagonists: states, TNCs and civil society.

This has seen TNCs ally with governments, predominantly from countries that host the largest transnational corporations on one side, while social movements ally with some supportive governments from the Global South at the same time as urging governments of the Global North to participate actively and constructively in the process.

TNCs assert their interests and influence through their associations and as ‘civil society’ organisations with ECOSOC status at the UNHRC, where they are represented through the ICC and the IOE, which is also represented in the tripartite International Labour Organization (ILO).

Both organisations present their perspectives in the panels and conferences of the OEIGWG meetings, and also take the floor during the sessions and submit written positions in the formal process. They have consistently claimed that the proposed treaty will have a negative impact on investment in developing countries – a position also reflected by pro-corporate lawyers and academics at the UNHRC.

There has been a longstanding debate on why the ICC and IOE are classified as CSOs with ECOSOC status, especially given their conflict of interest with an agenda focused on human rights and corporate accountability. By comparison, the World Health Organization (WHO) Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (FCTC) excludes tobacco corporations in the bodies implementing the FCTC as a result of campaigns exposing corporate funding of so called ‘independent’ research.

In tandem with their direct interventions, TNCs present themselves as models of ‘good practice’ in relation to human rights at the Annual Forum on Business and Human Rights at the UNHRC in Geneva. The aim of this event is to show that voluntary self-regulation works and that binding treaty obligations are an unnecessary burden, which is belied by its members’ practices.

The Brazilian mining company Vale, for instance, attended several Annual Forums, despite its disregard for safety standards resulting in two dam collapses – releasing millions of tonnes of toxic waste and mud from mining operations at Mariana (November 2015) and Brumadinho (January 2019) in the state of Minas Gerais. It is estimated that hundreds of people died as a result of the devastation, and the poisoning of rivers and land is among Brazil’s worst environmental disasters.

Communities in Mariana demanding justice and reparations. Photo credit: Yuri Barichivich / Greenpeace

The influence and success of corporate lobby is evident in the way the discourse is echoed by the US, EU member states and other Northern states – with the backing of states from other regions, particularly the current right-wing governments in Chile, Colombia and Guatemala. Their shared discourse, approach and tactics towards the Binding Treaty process is to do everything possible either to block it or render it meaningless.

Even if the full implications of corporate capture at the UN remain obscure, many concerns have been raised on how this plays out in relation to the UN mechanisms on human rights. For instance, the agreement between Microsoft and the High Commissioner for Human Rights in 2015 was seen as a classic case of a non-transparent corporate donation. Coming as it did in the first year of the OEIGWG process – a highly sensitive time in relations between TNCs and affected communities – the absence of full disclosure on its purpose was questioned.

The obstructive tactics of the corporations–states nexus range from rhetorical to procedural and political.

The rhetorical approach has been most evident in the introduction of the Global Compact and the UNGPs. The adoption of the UNGPs in 2011 has been treated as a basis for rejecting other approaches until these have been properly implemented. They are also claimed to be more ‘legitimate’ since they were adopted by consensus whereas a binding treaty will require a voting process. It is also asserted that they are more legitimate than a process led by states that have their own shortcomings in respecting human rights.

One key discursive battle concerns the scope of a potential treaty, with the EU pushing from the beginning to include ‘all business enterprises’. At first sight, this looks reasonable: many states and CSOs believe that the treaty provisions should also be applied to small and medium enterprises (SMEs). That said, SMEs are covered under national legislation, whereas there is a major legal gap in international law that legitimates and protects the impunity of TNCs. Because of strong legal protection of their ‘rights and privileges’ through Trade and Investment Agreements, their mobility, vast economic power and increasing political influence, TNCs continue to operate with impunity.

The major asymmetry of power and structure between TNCs and SMEs requires a different approach. This concern has been frequently raised by Southern states that have no national flagship TNCs and whose economies are mainly led by SMEs that are subject to domestic laws and which – unlike ‘mobile’ TNCs – cannot escape accountability. For this reason, many interpret the EU’s position as a tactic to derail the process.

At the procedural level, the most serious challenge has been to the position of the OEIGWG chair and the body’s function as a state-led process. The EU in particular has also strongly argued for the chair to be occupied by an ‘expert’, similar to the UNGP process. The EU delegation has also tried other diversionary tactics, such as delaying sessions by threatening not to adopt the plan of work or complaining about the lack of adequate consultation in drafting the texts.

At the political level, there has been explicit pressure applied on developing countries. Calls to embassies and meetings have been reported informally, including threats of cuts in investments or aid. Similarly, in 2015 at the 5th Committee of the UNGA (which approves the UN budget each December), EU member states threatened to block the approval of the budget for the functioning of the OEIGWG. The rapid mobilisation and response of the G77 countries and the pressure of CSOs helped protect this essential budget allocation for 2016.

In the OEIGWG sessions, the European External Action Service (EEAS) – which represents the EU at the UNHRC– has repeatedly asserted a common EU position, ignoring several European Parliament (EP) Resolutions that have been far more supportive of a binding treaty.

For example, the 2018 EP Resolution ‘warmly welcomes in this context the work initiated in the United Nations through the OEIGWG to create a binding UN instrument on transnational corporations and other business enterprises with respect to human rights, and considers this to be a necessary step forward in the promotion and protection of human rights’.

Members of the EP (MEPs) together with some MPs from the South set up the Global Interparliamentarian Network (GIN), now comprising over 300 members. Its representatives have participated in all Sessions of the OEIGW process and have co-organised side events.

Against the efforts of the corporations and their allied states, social movements and some Southern governments have mobilised actively to maintain momentum. CSOs submitted dozens of written proposals and opinions during all four sessions, and made many interventions from the floor linking specific situations with the need for a binding treaty and proposing specific changes to the official texts.

They have also consistently engaged representatives of all government Missions at the UNCHR and to the OEIGWG chair in advocacy meetings and Side Events. Recently, a group of interested countries and organisations from the Global Campaign have begun a series of informal ‘policy dialogues’ to explore common positions and strategies towards achieving a meaningful treaty.

The process has been continuously energised by resistance struggles on the ground – whether against oil and gas extraction and contamination, land and ocean grabs, mega dam collapses, poisoning of water and land, forest fires, or the fall-out from the textile and pharma industries.

Each experience showed the urgent need for an international instrument to protect the rights of affected peoples and direct victims. Meanwhile, the denial of justice in longstanding cases such as Union Carbide, Chevron, and also in the more recent cases of Rana Plaza, Lonmin and Vale, demonstrate that the existing system is not working.

Gaining traction at every session

The result of this mobilisation has been that the process has moved forward despite countless attempts to derail it – not simply holding its ground, but gaining traction with 90–100 states participating in the 2018 and 2019 Sessions.

By the third Session (2017) the initial Elements of a Treaty began to be discussed. A Zero Draft led the talks at the fourth Session (2018) and a Revised First Draft was thoroughly discussed during the fifth Session (14–18 October 2019). The programme of work covered all 22 articles – in a constructive dynamic that heard many substantive contributions from more than 30 states, as well as parliamentarians, experts, affected communities and civil society.

The 22 articles of the Revised First Draft include a basic set of framework provisions – several with potential to facilitate access to justice. The text proposes more effective mechanisms for mutual legal assistance among states as well as international cooperation, and a proposal that could open up new possibilities of ‘extra territorial obligations’ – that is, states’ obligations in relation to crimes committed by their TNCs in another state’s jurisdiction. There is also reference to the ‘legal liability’ of enterprises although the proposal is unclear about whether this refers to administrative or civil liability.

In terms of prevention, the text mainly relies on the idea of ‘due diligence’ – in vogue since the adoption of the UNGPs. France has recently passed a ‘duty-of-vigilance’ law, although its impact has yet to be seen. In October 2019, an important test case was launched against Total, the formerly French oil company, for violating the rights of communities in its operations in Uganda.

Likewise, the Revised First Draft’s provisions on the rights of victims could be the basis for further development, especially if it is extended to include a broader definition of ‘affected communities or people’, as the Movement of People Affected by Dams (MAB) in Brazil proposed from the outset.

A Conference of State Parties and a Treaty Body have been proposed to follow the adoption, implementation and improvement of the Treaty. These are standard UN procedures and are often useful, but to date have been used mainly to denounce states and not to enforce Treaty provisions in relation to TNCs.

Nevertheless, the conclusion of the 5th Session means that the debate is no longer about whether there is a need for such a Treaty and legally binding instrument that addresses TNCs’ evident impunity and decisively opens the door to justice for affected communities.

For the first time, states and all other actors have to position themselves, study and explain the basis of their proposals based on content and address some hard questions.

How do we define the obligations of states and of TNCs? What mechanisms and instruments are needed to enforce the Treaty? How do we define TNCs and the implications for ‘all other businesses’? What role should the state play in implementing the Treaty? And what are the rights of victims and affected communities to obtain justice?

The Achilles' heel in the Draft Treaty

From the perspective of affected communities and social movements, the main controversial articles appear in the first three sections of the Revised Draft. The first relates to the definition of TNCs and their supply chains and related ‘contractual relationships’; the second is the extension of the scope of the treaty to ‘all business enterprises’; and the third is the reiteration of the state-centred approach to responding to human rights violations – each of which could be an Achilles’ heel in this 2019 draft.

The state-centred approach implicitly negates the idea that TNCs have direct obligations and responsibilities related to human rights at international level. This has been a central demand of the Global Campaign as it would mean that an affected community or person could have recourse to international jurisdiction regarding violations derived from the operation of TNCs. In this scenario, a dedicated International Court could, for instance, make a judgement against Chevron in the case of the Ecuadorian Indigenous People (UDAPT) and the contamination of their region by the oil company’s operations.

This proposal is still strongly contested by TNCs and some states and, even if many see it as a necessary evolution of human rights in a globalised world, others feel it threatens well established human rights doctrine. The latter defines the state as the only entity with obligations in the current international human rights framework – which is why many argue that only states – the duty bearers – ‘violate’ human rights.

The international human rights regime may not yet be ready for the major changes demanded by a meaningful Binding Treaty on TNCs and so may explore other alternatives – for instance, stronger extra-territorial obligations, or inter-jurisdictional cooperation. Although these are important measures that would shift the status quo, they would not respond to the positions advanced by affected communities.

The current text does not include other substantive elements that have also been advocated by the Global Campaign, and in official submissions: among them the clear supremacy of human rights over trade and investment agreements; the centrality of the rights of affected communities – including clear mechanisms for consultation, risk assessments and impacts, as well as for research and investigation of situations that could potentially involve violations before they happen; a stronger gender perspective; and extended penal liability of the company along its supply and value chains and its subsidiaries, including those responsible for decision-making and overall corporate management and policy.

Navigating the challenges ahead

In almost 50 years of international attempts to end TNC violations of human rights and environmental standards, this is the first time that affected peoples and civil society constituencies from six continents are actively engaged and in significant numbers.

This participation has been constant and growing since 2013, when the first joint statement by the Global Campaign was released. This marks a significant step forward from earlier important processes in the area of binding regulations on TNCs.

Not even the UNHRC Peasants’ Rights Declaration process and debates generated the same traction and participation as the OEIGWG has achieved in the past five years. Committed states are still too few, while powerful forces are working to derail and block the process.

But five years on, as the negotiations have resisted being undermined, ever more states, parliamentarians, experts, scholars – and of course, leaders and activists of affected communities, social movements and civil society – are engaging in the process. Recently, even Professor Ruggie recognised this at a Finnish government conference where he criticised the EU for not taking a supportive position on the binding treaty, which he said ‘is inevitable and desirable’.

The process to establish a Binding Treaty on TNCs has gained momentum against all the odds and already changed minds – busting the myth that TNCs are ‘untouchable’ and helping to dismantle corporate power in the current phase of capitalism.

This is already a significant victory, moving into terrain beyond the self-regulation and UNGPs previously proposed by Ruggie. It moves us towards the central demand of affected communities, one that rejects corporate rule.

Whatever the eventual outcome, this joint effort of states and affected communities has articulated a key issue, the answer to which will define the coming decades for humanity and the planet. We are at the edge of a new epoch where new and radical transformation will be necessary to address the intensifying contradictions within the economy, politics and our relations with nature.

This Binding Treaty initiative is integral to a needed transformation and part of those ongoing struggles. The question is whether it will finally generate the convergence of forces and political will to address it.

- Brid Brennan co-ordinates the Corporate Power project at the Transnational Institute. She has extensive experience of working with social movements and affected communities and their struggles throughout the global South challenging the economic and political power of transnational corporations. She collaborates with the Transnational Migrant Platform-Europe which addresses the massive displacement caused by corporate operations, war and climate change and advocates for the fundamental human rights of migrant and refugee people.

- Gonzalo Berrón, TNI Associate Fellow, has played a leading role in coordinating Latin American movements resisting corporate "Free Trade Agreements." He has been an integral part of ongoing discussions with civil society and progressive governments on building alternative just regional trade and financial architecture in Latin America.

Source: TNI, State of Power 2020 https://longreads.tni.org/touching-a-nerve/

Del mismo autor

- It Is Not a Crime to Migrate or Seek Refugee – It is a Human Right! 23/12/2020

- ¡Migrar o buscar refugio no es un crimen! ¡Es un derecho humano! 23/12/2020

- Tratado sobre ENTs y derechos humanos: Un punto sensible 08/06/2020

- Treaty on TNCs and human rights: Touching a nerve 31/01/2020

- Fatal blows to corporate power 23/01/2017

- Golpes mortais contra o poder corporativo 13/01/2017

- Golpes mortales al poder corporativo 12/12/2016

- Soberanía de los Pueblos versus Impunidad S.A. 07/07/2015

- Es hora de exigir un tratado vinculante sobre las transnacionales 23/06/2014

- Reunión de la ONU crea oportunidad histórica para poner fin a la impunidad de las transnacionales 23/06/2014