The Politics of Internet Governance: Imperialism by Other Means

The USA is deliberately structuring Internet governance to ensure unrestricted corporate freedom and to favour its own surveillance apparatus to support its foreign policy.

- Opinión

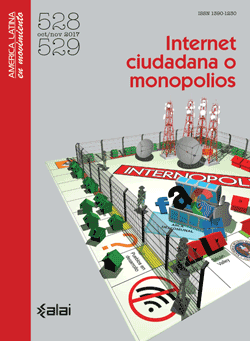

| Article published in ALAI’s magazine No. 528: Internet ciudadana o monopolios 16/11/2017 |

The USA is deliberately structuring Internet governance to ensure unrestricted corporate freedom and to favour its own surveillance apparatus to support its foreign policy[1], under the guise of “combating terrorism”. By the same token, it largely denies that certain services should be public services (or public goods); and rejects any government role in supervising, much less regulating, the Internet.

Our increasing reliance on Information and Communication Technologies (ICTs), which include the use of transnational networks to interconnect personal computers and business computer systems, has important consequences for governments[2] and all lines of commerce, in particular finance. The current information revolution is far more significant than the previous changes induced by telegraphy or telephony.[3] While policy makers worldwide grasp this, most do not fully see the power implications. In contrast, US policy makers understand the importance of networks such as the Internet in promoting their country’s geo-economic and geo-political goals.[4]

Many aspects of the Internet continue to be governed by ad hoc entities dominated by US economic interests (or at least those of developed countries), in ways that are almost entirely beyond the control of existing institutions such as the UN’s specialized ICT agency, the International Telecommunication Union (ITU), and beyond the control of any national government except the USA.[5]

The power implications of this situation are evident: the US and the private companies it backs have far more say regarding the global Internet than anybody else. And they use this power for political ends (e.g. mass surveillance) and for economic ends (e.g. the very high profits reaped by companies such as Google).[6] For sure the US accepts some international discussions, but only in forums which it expects to dominate, and only to the extent that the discussions conform to its expectations. Indeed the US openly uses its political power in the forums where these matters are discussed, attempting to impose trade and investment policies that will favour its private companies, blatant examples being discussions within the World Trade Organization (WTO), the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP), the Transatlantic Investment and Trade Partnership (TIPP), and the Trade in Services Agreement (TiSA).

And it uses a human rights discourse, in particular freedom of speech and the spectre of other governments attempting to control the Internet for censorship reasons or to stifle innovation, to mask its own human rights violations, in particular the denial of democratic governance, the imposition of US laws on the citizens of foreign countries and mass surveillance. Moreover the trade deals that the US is using to further corporate interests stymie aspirations for transnational economic equity.

Despite much rhetoric about openness, participation, accountability, and democracy, the current governance model (called “the multi-stakeholder model”) is largely undemocratic, because it is dominated by a professional coterie of representatives of commercial and political interests.[7] And it has been unable to address key Internet issues such as security and affordability of access in developing countries.

The USA’s relinquishing of its last vestiges of control over the management and administration of Internet names and addresses (the IANA transition) is being touted as a successful paradigm to apply to other walks of life, but in reality it is just another privatization that allows private companies to control and exploit what should be public resources.[8]

Meanwhile the rest of the world sits on the sidelines, unaware of the stakes or unable to weigh into the debate. After all, why would anybody be concerned about this power imbalance as long as access to the Internet continues to expand; email and the Web remain apparently open; social media is deployed in ever more creative ways; and innovative “free” services become increasingly available?

We should be worried because there are no free services: users pay for the services they receive by providing data, which is monetized and used to generate revenues that are far in excess of the value of the services provided.

As my colleague Parminder Jeet Singh and I have put the matter[9]: “A global digital order is slowly taking shape but while the North is developing the norms and policy principles for this order on the basis of its own interests, the developing world remains at the margins of this process. Unless they get their act together, the developing countries risk being locked into a digital dependency which will ultimately impact on their national sovereignty.”

And thus, not surprisingly, the Internet is being used as a tool for economic and political dominance, that is, imperialism - just as, in the past, other means of communication such as roads and telegraphy were used by empires in their own interest[10].

In this light, we call on all to join the Internet Social Forum, as described in the the concept paper: Why the Internet's future needs social justice movements; and to endorse the Delhi Declaration of the JustNet Coalition.

Richard Hill is president of the Association for Proper Internet Governance.

This paper is largely taken from previous paper "The True Stakes of Internet Governance", State of Power 2015, Transnational Institute, January 2015. A Spanish version was published in ALAI's magazine América Latina en Movimiento, No. 528-529, Oct-Nov 2017 https://www.alainet.org/es/revistas/528-529

[1] Powers, Shawn and Jablonski, Michael (2015), The Real Cyber War: The Political Economy of Internet Freedom, University of Illinois Press

[2] An excellent analysis of the issues arising from this situation is given in Hathaway, Melissa, 2014. “Connected Choices: How the Internet is Challenging Sovereign Decisions”, American Foreign Policy Interests, vol. 36, no. 1, p. 300 <http://belfercenter.ksg.harvard.edu/publication/24689/connected_choices....

[3] Powers and Jablonski (2015)

[4] Schiller, Dan (2014), Digital Depression: Information Technology and Economic Crisis, Urbana: University of Illinois Press

[5] Hill, Richard (2013), "Internet governance: the last gasp of colonialism, or imperialism by other means", in Rolf H. Weber, Roxana Radu, and Jean-Marie Chenou (eds), The evolution of global Internet policy: new principles and forms of governance in the making?, Schulthess/Springer

[6] See for example the 2013-2014 annual report of IT For Change <http://www.itforchange.net/ITfC_Annual_Report_2013-14/index.php/Main_Page>

[7] Powers and Jablonski (2015)

[8] Hill, R. (2017) "Internet governance, multi-stakeholder models, and the IANA transition: shining example or dark side?", Journal of Cyber Policy, Vol. 1, No. 2

[9] Hill, R. and Singh, P.J. (2017)“Digitalisation and the gig economy: Implications for the developing world" (with Parminder Jeet Singh), Third World Resurgence, no. 319/320 (Mar/Apr 2017)

[10] See for example Hills, J. (2007) Telecommunications and Empire, University of Illinois Press

Del mismo autor

- A new convention for data and cyberspace 07/05/2021

- Una convención sobre los datos y el ciberespacio 06/05/2021

- Trump and CDA Section 230: The End of an Internet Exception? 31/07/2020

- Governing the digital world: Lessons from last year’s WTO Public Forum 23/01/2020

- Data as a commodity 30/07/2019

- Some thoughts on cyber-war 28/09/2018

- Reflexiones sobre la ciberguerra 27/09/2018

- The Politics of Internet Governance: Imperialism by Other Means 29/11/2017

- La política de la gobernanza de Internet: el imperialismo por otros medios 28/11/2017

- Necesitamos normas internacionales vinculantes para las ETN digitales 26/10/2017

Clasificado en

Comunicación

- Jorge Majfud 29/03/2022

- Sergio Ferrari 21/03/2022

- Sergio Ferrari 21/03/2022

- Vijay Prashad 03/03/2022

- Anish R M 02/02/2022

Internet ciudadana

- Nick Bernards 31/03/2022

- Paola Ricaurte 10/03/2022

- Burcu Kilic 03/03/2022

- Shreeja Sen 25/02/2022

- Internet Ciudadana 16/02/2022